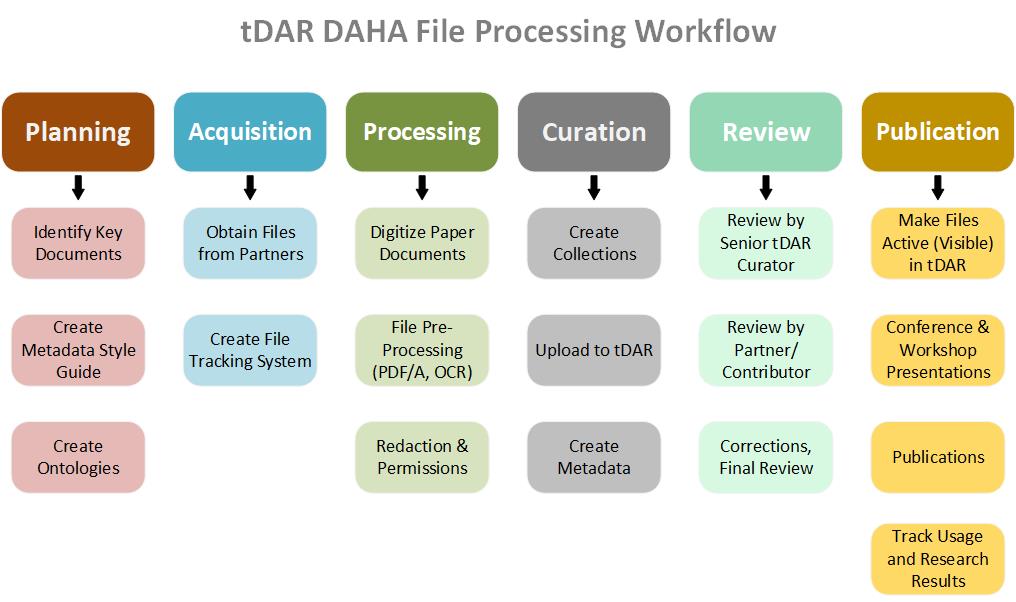

Digital Antiquity staff developed a comprehensive and reliable digital curation workflow designed to process DAHA documents in a consistent, timely and cost‐effective manner. This ensured quality control and helped to maximize the research value of the DAHA Archive.

Planning, Document Selection and Acquisition

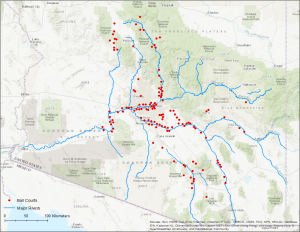

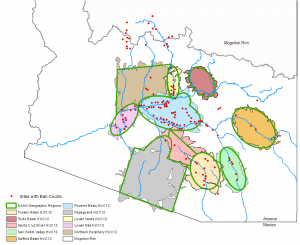

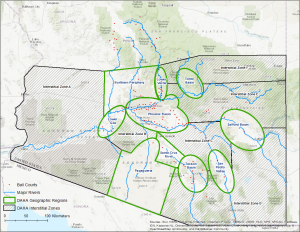

DAHA project leaders identified and contacted more than 15 organizations that are, or have been, major producers of Huhugam research and analysis. Selection focused particularly on organizations that had important collections of unpublished grey literature reports. A majority of the projects undertaken in the U.S. over the last 50 years have been carried out by commercial firms or government agencies and reported only as unpublished grey literature. These documents are extremely valuable because they are professionally written, rich in technical detail, and carefully edited but distributed—usually in paper—in very small numbers. Our success in addressing some of archaeology’s most important questions hinges on our ability to gain access to this wealth of information. The inclusion of more than 2,000 grey literature documents in DAHA provides easy access as well as preservation into the future.

The other selection criterion was a focus on project reports and analyses, rather than field notes or artifact lists. Partner organizations were asked to identify relevant Huhugam documents and data sets in their possession, ones that they were willing to contribute to tDAR for public access. Since our partners provided paper reports as well as digital files, a file tracking system was established to monitor the different paper vs digital curation steps (see below).

As a final planning step, a DAHA Metadata Style Guide was created to promote consistency among the various digital curators working on the project. A style guide is a document that provides specific instructions and examples for each tDAR descriptive metadata element (https://www.tdar.org/using-tdar/upload-toolkit/#developingAMetadataStyleGuideData). The DAHA style guide ensured that each document was richly described using a shared vocabulary so that similar or related documents are linked to each other in tDAR.

Processing and Digital Curation

Once selected and acquired, paper documents entered a standard processing workflow, a series of efficient, well-documented steps that could be carried out by student workers as well as Digital Antiquity staff members. If the report was born digital, the same processing steps were followed starting at Step 4. These steps included:

- Unbind (if necessary);

- Scan using a sheet-feeder and appropriate dpi settings;

- Scan rare or valuable reports using a book scanner;

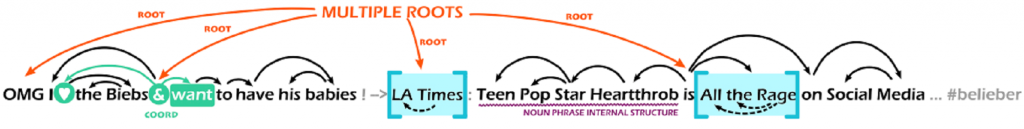

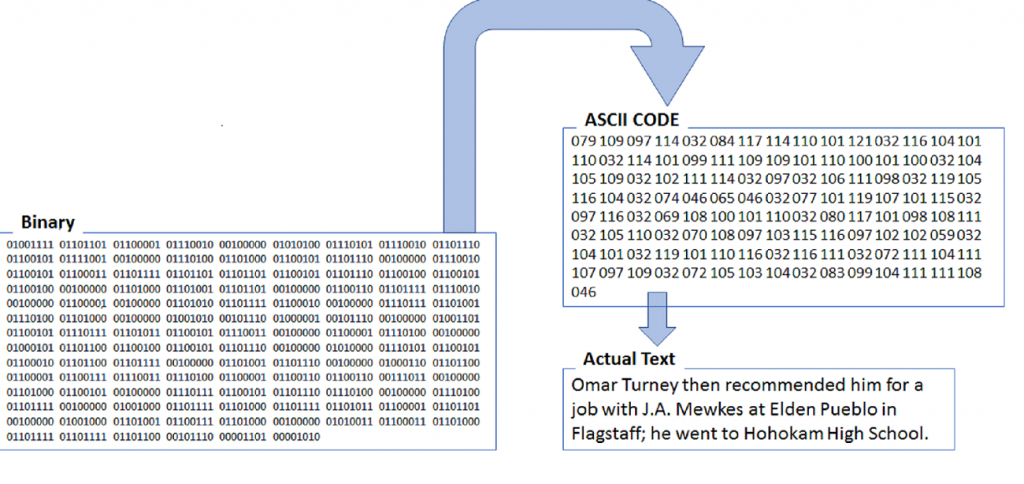

- Optical Character Recognition (OCR) using ABBYY FineReader;

- Convert to PDF/A;

- Review for confidential and/or sensitive material and redact if necessary;

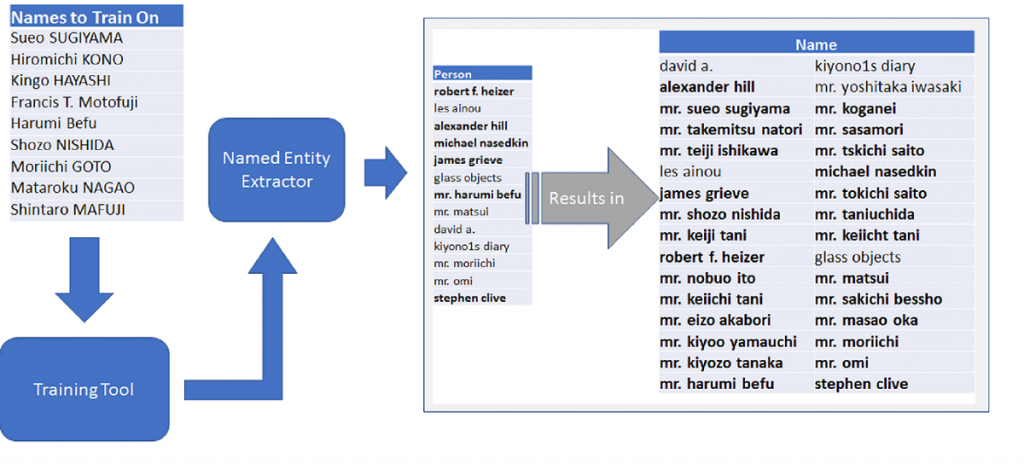

- Create metadata based on the tDAR basic metadata schema and the DAHA Style Guide;

- Upload the original file and the redacted PDF/A to tDAR.

Metadata entry is a key part of the curation workflow. tDAR has an interactive interface that standardizes entry of bibliographic and descriptive metadata, provides tools to identify geographic and temporal contexts, and has menus to add contact information for associated individuals and organizations.

Finally, DAHA was organized into a number of overlapping collections, each of which may have sub‐collections. A collection identifies a logical grouping of related tDAR files and aids discovery and resource administration. For example, a collection has been created for each partner organization; other collections have been built topically.

Review

All documents were reviewed by digital curators to correct scanning or metadata errors, but also to determine whether the document contained sensitive or confidential information. Confidential information is information that should have restricted dissemination due to the reasonable risk of vandalism or looting of archaeological resource(s). The Archaeological Resource Protection Act (ARPA) and the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) restrict the release of information about specific locations and/or characteristics of sites covered by these laws if the public release of such information might result in damage to or loss of the site. Sensitive information is information that may be culturally offensive to some individuals or groups. The Center for Digital Antiquity has a “Treatment of Confidential and Sensitive Content in the Digital Archive of Huhugam Archaeology” document that outlines the DAHA review process, available on the DAHA website.

During review, sensitive or confidential content was flagged and redacted. An unredacted version of each document was preserved and a redacted copy created. The unredacted version was uploaded to tDAR but marked as confidential and access restricted. The redacted copy was uploaded and is the version that is visible in tDAR and available for download.

As a final review, the partner organization that contributed the file was invited to review the document, any redaction (if present) and all metadata. Files remained in “Draft” form until completion of the full review process. Draft documents and metadata records are not publicly visible or accessible. Only after the review process was completed were documents made visible (Active) in tDAR.

Publication, Dissemination and Outcome Tracking

Once the review process was completed, DAHA staff changed each document’s status to “Active,” making it visible and available for download. The metadata related to public files in tDAR is indexed by search engines like Google, increasing the findability of the DAHA corpus.

A variety of approaches were taken to help publicize and disseminate the DAHA library. One important communication venue was the DAHA project website. The website was created during the first year of the project as a means of publicizing results and facilitating communication with various user communities. The Center for Digital Antiquity will continue to host the website as a useful companion to the Archive in tDAR. In addition to answering common user questions, the FAQ page provides a mechanism for users to send feedback about the site, ask additional questions, or contribute new material to DAHA. The blog posts and news items provide detailed descriptions of various aspects of the project

Digital Antiquity collects anonymized download and usage data that allows us to track how people discover and use the records in tDAR. Over the next several years Digital Antiquity staff will compare usage data for DAHA files (e.g., downloads, links, and views) with average usage metrics for other collections. This will help track the success of the DAHA library and also help evaluate the success of conference presentations, public presentations and other DAHA related publication events.

DAHA project staff will prepare articles targeted to communities of interest, such as Archaeology Southwest and the Arizona Archaeological Council Journal of Arizona Archaeology. Project staff will also submit articles to The SAA Archaeological Record, Advances in Archaeological Practice, and Digital Humanities Quarterly. Finally, papers will be presented at annual meetings of the Society for American Archaeology. In calendar year 2022, DAHA staff will host an Arizona Archaeological Council workshop exploring the research uses of the DAHA corpus.